F1 CARS 25

1. INTRODUCTION

Car racing is one of the most technologically advanced

sports in the world today. Race Cars are the most sophisticated vehicles that

we see in common use. It features exotic, high-speed, open-wheel cars racing

all around the world. The racing teams have to create cars that are flexible

enough to run under all conditions. This

level of diversity makes a season of F1 car racing incredibly exciting. The

teams have to completely revise the aerodynamic package, the suspension

settings, and lots of other parameters on their cars for each race, and the

drivers have to be extremely agile to handle all of the different conditions

they face. Their carbon fiber bodies, incredible engines, advanced aerodynamics

and intelligent electronics make each car a high-speed research lab. A F1 Car

runs at speeds up to 240 mph, the driver experiences G-forces and copes with

incoming data so quickly that it makes

Car driving one of the most demanding professions in the sporting world. F1 car is an amazing machine that pushes the

physical limitations of automotive engineering. On

the track, the driver shows off his professional skills by directing around an

oval track at speeds

Formula One Grand Prix racing is a glamorous sport where a

fraction of a second can mean the difference between bursting open the bubbly

and struggling to get sponsors for the next season's competition. To gain those

extra milliseconds, all the top racing teams have turned to increasingly

sophisticated network technology.

Much more money is spent in F1 these days. This results

highest tech cars. The teams are huge and they often fabricate their entire

racers. F1's audience has grown tremendously

throughout the rest of the world. .

In an average street car equipped with air bags and

seatbelts, occupants are protected during 35-mph crashes into a concrete

barrier. But at 180 mph, both the car and the driver have more than 25 times

more energy. All of this energy has to be absorbed in order to bring the car to

a stop. This is an incredible challenge, but the cars usually handle it

surprisingly well

F1 Car driving is a demanding sport that requires precision,

incredibly fast reflexes and endurance from the driver. A driver's heart rate

typically averages 160 beats per minute throughout the entire race. During a

5-G turn, a driver's arm -- which normally weighs perhaps 20 pounds -- weighs

the equivalent of 100 pounds. One

thing that the G forces require is constant training in the weight room.

Drivers work especially on muscles in the neck, shoulders, arms and torso so

that they have the strength to work against the Gs. Drivers also work a great

deal on stamina, because they have to be able to perform throughout a

three-hour race without rest. One thing that is known about F1 Car drivers is that they

have extremely quick reflexes and reaction times compared to the norm. They

also have extremely good levels of concentration and long attention spans.

Training, both on and off the track, can further develop these skills.

2. THE CHASIS

Modern

f1 Cars are defined by their chassis. All f1 Cars share the following

characteristics:

They are single-seat cars.

They have an open cockpit.

They have open wheels -- there are no

fenders covering the wheels.

They have wings at the front and rear

of the car to provide downforce.

They position the engine behind the

driver.

The

tub must be able to withstand the huge forces produced by the high cornering

speeds, bumps and aerodynamic loads imposed on the car. This chassis model is

covered in carbon fibre to create a mould from which the actual chassis can be

made. Once produced the mould is smoothed down and covered in release agent so

the carbon-fibre tub can be easily removed after manufacture.

The

mould is then carefully filled inside with layers of carbon fibre. This

material is supplied like a typical cloth but can be heated and hardened. The

way the fibre is layered is important as the fibre can direct stresses and

forces to other parts of the chassis, so the orientation of the fibres is

crucial. The fibre is worked to fit exactly into the chassis mould, and a hair

drier is often used to heat up the material, making it stick, and to help bend

it to the contours of the mould. After each layer is fitted, the mould is put

into a vacuum machine to literally suck the layers to the mould to make sure

the fibre exactly fits the mould. The number of layers in the tub differs from

area to area, but more stressed parts of the car have more, but the average

number is about 12 layers. About half way between these layers there is a layer

of aluminum honeycomb that further adds to the strength.

Once

the correct numbers of layers have been applied to the mould, it is put into a

machine called an autoclave where it is heated and pressurized. The high

temperatures release the resin within the fibre and the high pressure (up to

100 psi) squeezes the layer together. Throughout this process, the fibres

harden and become solid and the chassis is normally ready in two and a half

hours. The internals such as pedals, dashboard and seat back are glued in place

with epoxy resin and the chassis painted to the sponsor’s requirements.

3. COCKPIT

The

cockpit of a modern F1 racer is a very sparse environment. The driver must be

comfortable enough to concentrate on driving while being strapped tight into

his seat, experiencing G-forces of up to 5G under harsh braking and 4G in fast

corners.

GENERAL COCKPIT ENVIRONMENT

Every

possible button and switch must be close at hand as the driver has limited

movement due to tightness of the seat belts. The cockpit is also very cramped,

and drivers often wear knee pads to prevent bruising. The car designers are

forever trying to lower the centre of gravity of the car, and as each car has a

mass of 600 Kg, with the driver's being roughly 70 Kg, he is an important

factor in weight distribution. This often means that the drivers are almost

lying down in their driving position. The trend towards high noses led one

driver to comment that his driving position felt like he was lying in the bath

with his feet up on the taps!

As

the driver sits so low, his forward visibility is often impaired. Some of the

shorter drivers can only see the tops of the front tyres and so positioning his

car on the grid accurately can be a problem. You may see a mechanic holding his

hand where the top of the front tyre should stop during a pit-stop to help the

driver stop on his correct mark. Rear view mirrors are angled to see through

the rear wing and drivers often like to set them so that they can just see the

rear wheel.

Around

the drivers head there is a removable headrest / collar. This was introduced in

an attempt to protect the driver’s neck in a sideways collision. Some driver’s

also wear knee pads to prevent their knees banging together during hard

cornering.

4. AERODYNAMICS

One of the most important features of

a formula1 Car is its aerodynamics package. The most obvious manifestations of

the package are the front and rear wings, but there are a number of other

features that perform different functions. A formula 1 Car uses air in three

different ways introduction of wings. Formula One team began to experiment with

crude aerodynamic devices to help push the tires into the track.

4.1 WINGTHEORY

The wings on an F1 car use the same

principle as those found on a common aircraft, although while the aircraft

wings are designed to produce lift, wings on an F1 car are placed 'upside

down', producing downforce, pushing the car onto the track. The basic way that

an aircraft wing works is by having the upper surface a different shape to the

lower. This difference causes the air to flow quicker over the top surface than

the bottom, causing a difference in air pressure between the two surfaces. The

air on the upper surface will be at a lower pressure than the air below the

wing, resulting in a force pushing the wing upwards. This force is called lift.

On a racing car, the wing is shaped so the low pressure area is under the wing,

causing a force to push the wing downwards. This force is called downforce.

As air flows over the wing, it is

disturbed by the shape, causing what is known as form or pressure drag.

Although this force is usually less than the lift or downforce, it can

seriously limit top speed and causes the engine to use more fuel to get the car

through the air. Drag is a very important factor on an F1 car, with all parts

exposed to the air flow being streamlined in some way. The suspension arms are

a good example, as they are often made in a shape of a wing, although the upper

surface is identical to the lower surface. This is done to reduce the drag on

the suspension arms as the car travels through the air at high speed.

The

reason that the lower suspension arm has much less drag is due to the aspect

ratio. The circular arm will suffer from flow separation around the suspension

arm, causing a higher pressure difference in front of and behind the arm, which

increases the pressure drag. This occurs because the airflow has to turn

sharply around the cylindrical arm, but it cannot maintain a path close to the

arm due to the speed of the flow, causing a low pressure wake to form behind

it. The lower suspension arm in the diagram will cause no flow separation as

the aspect ration between the width and the height is much greater, and the

flow can maintain the smooth path around the object, creating a smaller

pressure difference between the air in front of the arm and the air behind. In

the bottom case, the skin friction drag will increase, but this is a minor

increase compared with the pressure drag.

4.2 REARWING

As

more wing angle creates more downforce, more drag is produced, reducing the top

speed of the car. The rear wing is made up of two sets of aerofoil connected to

each other by the wing endplates. The top aerofoil top provides most of the

downforce and is the one that is varied the most from track to track. It is now

made up of a maximum of three elements due to the new regulations. The lower

aerofoil is smaller and is made up of just one element. As well as creating

downforce itself, the low pressure region immediately below the wing helps suck

air through the diffuser, gaining more downforce under the car. The endplates connect

the two wings and prevent air from spilling over the sides of the wings, maximizing

the high pressure zone above the wing, creating maximum downforce.

4.3 FRONTWING

Wing

flap on either side of the nose cone is asymmetrical. It reduces in height

nearer to the nose cone as this allows air to flow into the radiators and to

the under floor aerodynamic aids. If the wing flap maintained its height right

to the nose cone, the radiators would receive less air flow and therefore the

engine temperature would rise. The asymmetrical shape also allows a better

airflow to the under floor and the diffuser, increasing downforce. The wing main

plane is often raised slightly in the centre, this again allows a slightly

better airflow to the under floor aerodynamics, but it also reduces the wing's

ride height sensitivity. A wing's height off the ground is very critical, and

this slight raise in the centre of the main plane makes react it more subtlety

to changes in ride height. The new- regulations state that the outer thirds of

the front wing must be raised by 50mm, reducing downforce. Some teams have

lowered the central section to try to get some extra front downforce, at the

compromise of reducing the quality of the airflow to the underbody

aerodynamics.

As the wheels were closer to the chassis, the

front wings overlapped the front wheels when viewed from the front. This

provided unnecessary turbulence in front of the wheels, further reducing

aerodynamic efficiency and thus contributing to unwanted drag. To overcome this

problem, the top teams made the inside edges of the front wing endplates curved

to direct the air towards the chassis and around the wheels. Later on and throughout the season, many teams

introduced sculpted outside edges to the endplates to direct the air around the

front wheels. This was often included in the design change some teams

introduced to reduce the width of the front wing to give the wheels the same

position relative to the wing in previous years.

The

interaction between the front wheels and the front wing makes it very difficult

to come up with the best solution, and consequently almost all of the different

teams have come up with different designs! The horizontal lips in the middle of

the endplate help force air around the tyres, whilst the lip at the bottom of

the plate helps stop any high pressure air entering the low pressure zone

beneath the wing, as it is the low pressure here which creates the downforce.

The

relationship between the front wing and the track is a delicate one, with the

wing generally being more efficient the closer to the track that it is. A rule

states that the wing must be 40 mm above the ground, This means that as the

speed increased, a force was produced which bent the ends of the wings down

towards the track, making the wind more efficient in high speed corners. The

rules state that the wings must not be adjustable on the track got around this

because there was no rule concerning the stiffness of the wings.

4.4 BARGEBOARDS

They are mounted between the front wheels and

the side pods, but can be situated in the suspension, behind the front wheels.

Their main purpose is to smooth the turbulent airflow coming from the front

wheels, and direct some of this flow into the radiators, and the rest around

the side of the side pods.

They

have become much more three dimensional in their design, and feature contours

to direct the airflow in different directions. Although the bargeboards help

tidy the airflow around the side pods, they may also reduce the volume of air

entering the radiators, so reaching a compromise between downforce and cooling

is important.

4.5 DIFFUSER

Invisible

to the spectator other than during some kind of major accident, the diffuser is

the most important area of aerodynamic consideration. This is the underside of

the car behind the rear axle line. Here, the floor sweeps up towards the rear

of the car, creating a larger area of the air flowing under the car to fill.

This creates a suction effect on the rear of the car and so pulls the car down

onto the track.

The

diffuser consists of many tunnels and splitters which carefully control the

airflow to maximize this suction effect. As the exhaust gases from the engine

and the rear suspension arms pass through this area, its design is critical. If

the exhaust gases are wrongly placed, the car has changed its aerodynamic

balance when the driver comes on and off the throttle. Some teams have moved

the exhausts so that they exit from the engine cover instead to make the car

more stable when the driver comes on and off the throttle. The picture above

shows what the complex arrangement of tunnels look like at the back of the car:

5. ENGINE

With

ten times the horse-power of a normal road car, a Formula One engine produces

quite amazing performance. With around 900 moving parts, the engines are very

complex and must operate at very high temperatures. Engines are currently

limited to 3 litre, normally aspirated with 10 cylinders. These engines produce

approximately 900 - 850 bhp and are made from forged aluminum alloy, and they

must have no more than five valves per cylinder. In a quest to reduce the

internal inertia of the moving parts, some components have been manufactured

from ceramics. These materials are very strong in the direction they need to

be, but have a very low density meaning that it takes less force to accelerate

them, ideal for reducing the fuel consumption and efficiency of the engine. A

similar material, beryllium alloy has been used, but the safety of it has been

questioned.

6. WHAT MAKES THESE ENGINES DIFFERENT TO

ROAD CAR ENGINES?

You

can often see road cars with engines larger than three liters, but these don't

produce upwards of 750 bhp. So how do F1 engineers produce this amount of power

from this size of engine? There are many differences between racing and road

car engines that contribute to the large power difference.

F1 engines are designed to rev much

higher than road units. Having double the revs should double the power output

as there are twice as many engine cycles within a certain time. Unfortunately,

as the revs increase, so doe’s friction within the engine, so eventually, a

point is reached where maximum power will occur, regardless of the number of

revs. Running engines at high revs also increases the probability of mechanical

failure as the components within the engines are being more highly stressed.

Exotic

materials such as ceramics as mentioned earlier are employed to reduce the

weight and strength of the engine. A limit of what materials can be used has been

introduced to keep costs down, so only metal based (ferrous) materials can be

used for the crankshaft and cams. Exotic materials can reduce the weight, and

are often less susceptible to expansion with heat, but there can be draw backs.

Incorporating these materials next to ferrous materials can cause problems. An

exotic material such as carbon fibre will not expand as much as steel for

example, so having these together in an engine would ruin the engine, as they

run to such small tolerances. Although only 5% of the engine is built of such

materials (compared with roughly 1/3 rd Steel, 2/3 rds Aluminum) they still

make a worthwhile addition to power output.

6.1 AIRBOX

Just

above the driver's head there is a large opening that supplies the engine with

air. It is commonly thought that the purpose of this is to 'ram' air into the

engine like a supercharger, but the air-box does the opposite. Between the

air-box and the engine there is a carbon fibre duct that gradually widens out

as it approaches the engine. As the volume increases, it causes the air flow

slow down, raising the pressure of the air which pushes it into the engine. The

shape of this must be carefully designed to both fill all cylinders equally and

not harm the exterior aerodynamics of the engine cover.

6.2 FUEL & FUEL TANK

The

fuel tank, or 'cell', is located immediately behind the driver’s seat, inside

the chassis. The cell is made from two layers of rubber, nitrate butadiene,

with the outer layer being Kevlar reinforced to prevent tearing. The cell is

like a bag, it can deform without tearing or leaking. The cell is made to

measure exactly and is anchored to the chassis to prevent it moving under the

high g-forces. The inside of this tank is very complex and contains various

section to stop the fuel sloshing around, and there are up to three pumps

sucking out the fuel so to get every last drop. These pumps then deliver the

fuel at a constant rate to the single engine fuel pump. The link between the

fuel tank and the engine is a breakaway connection so that the fuel flow is

stopped automatically if the engine is ripped off the chassis in a large

accident. Sizes of fuel tanks vary, but normally fuel cell holds 135 litres.

6.3 EXHAUSTS

Exhausts

are important to remove the waste gases from the engine, but they also play a

part in determining the actual power of the engine. Due to the complicated

harmonics within the engine, exhaust length can directly alter the power

characteristics as pressure waves flow through the exhaust and back to the engine.

Making sure these pulses are in time with the engine will enable more air to be

sucked into the engine, hence more power. Now Introduced exhausts that exited through

the top of the engine cover above the gearbox (These are commonly called

periscope exhausts due to their shape). Previously, all teams had the exhausts

exiting through the diffuser, but this could alter the amount of downforce

developed depending on whether the driver was on the throttle or not. Cars that

use the periscope exhausts often have gold or silver film protecting the

suspension and lower rear wing from the high temperatures of the exhausts

gases.

Exhausts

also play a critical role in determining the shape of the rear of the car. If

the engine designers can make the exhausts as compact as possible, it allows

the 'Coke Bottle' shaped part of the car to start nearer the front of the side

pods, increasing the efficiency of the rear aerodynamics

6.4 COOLING SYSTEMS

F1Cars

have two fluids that require cooling oil, water and have a radiator set-up for

each. But as most race teams use radiators from their engine suppliers, there

is little they can do about their design. And, with the cooling fluids pumped

through at a rate specified by the engine company, all the teams can do here is

concentrate on obtaining the best airflow through to the radiator which is

achievable through duct design. The best position for a duct is in the side

pods either side of the engine, which is where the radiators are positioned.

Because Formula 1 cars rely on the airflow caused by their own motion for

cooling, they do not have cooling fans when the car is not moving, however, the

teams use small fans attached to bags of dry ice which are fitted to the front

of the side pods. These fans can often be seen in action on the starting grid

in order to maintain the optimum working temperature of the engine while the

car is stationary.

In

traveling through the duct, the air will pass through five areas. The first is

the inlet, which is designed to allow just the right amount of air to enter the

duct. They have to be side mounted due to the positioning of the radiators, and

with a low centre of gravity required, the lower to the floor these heavy items

are, the better the car will handle.

The

air which has entered the duct is then expanded in a 'diffuser' which increases

in cross sectional area, and is steered in the direction of the radiator. A

splitter is used in this section to bleed off the energy flow that develops on

the car body ahead of the inlet (the boundary layer) and grows as the air

travels along the surface. The diffuser must also be designed so that very

little boundary layer develops inside, as this will reduce the cooling

potential at the edges of the radiator. Once the high energy flow reaches the

radiator, the airflow undergoes the heat exchange, after which it is

accelerated in a 'nozzle' which increases in area before returning the air to

the airstreams at the duct exit.

The

positioning and size of the duct exit determines how much cooling air gets

through the side pods, and many teams have 'side outs' of adjustable size. Once

again, the type of track determines how big these need to be, as a circuit with

slower average speeds such as Internal aerodynamics is one of the most

important and overlooked aspects of racing car design. If the team doesn't put

its engine in as kind an environment as possible, its chances of lasting the

race are much reduced.

6.5 TRANSMISSIONS

Just

like in your family road car, F1 cars have a clutch, gearbox and differential

to transfer the 800 bhp into the rear wheels. Although they provide the same

function as on a road car, the transmission system in an f1 car is radically

different...

6.5.1 CLUTCH

The

engine is linked directly to the clutch, fixed between the engine and gearbox. Some

manufacturers produce Carbon/Carbon F1 clutches which must be able to tolerate

temperatures as high as 500 degrees. The clutch is electro-hydraulically

operated and can weigh as little as 1.5 kg.

They

are multi-plate designs that are designed to give enhanced engine pick-up and

the lightweight designs mean that they have low inertia, allowing faster gear

changes. The drivers do not manually use the clutch apart from moving off from

standstill, and when changing up the gears, they simply press a lever behind

the wheel to move to the next ratio. The on-board computer automatically cuts

the engine, depresses the clutch and switches ratios in the blink of an eye. In

F1 cars, clutches are 100 mm in diameter.

6.5.2 GEAR BOX

F1

car gearboxes are different to road car gearboxes in that they are

semi-automatic and have no synchromesh. They are sequential which means they

operate much like a motorcycle gearbox, with the gears being changed by a

rotating barrel with selector forks around it. The lack of a synchromesh means

that the engine electronics must synchronize the speed of the engine with the

speed of the gearbox internals before engaging a gear.

6.5.3 GEAR RATIOS

Each

team builds their own gearbox either independently or in partnership with

companies. The regulations state that the cars must have at least 4 and no more

than 7 forward gears as well as a reverse gear. Most cars have 6 forward gears,

although there is the start of a trend towards using seven. Seven speeds are

used if an engine has a narrow power band, having more ratios in the gearbox

keeps the engine working in this ideal band. The gearbox is attached to the

back of the engine via four or six high-strength studs, with both the engine

and gearbox being fully stressed members of the car. The suspension for the

rear wheels bolts directly onto the gearbox casing, carrying the full weight of

the rear of the car. As a result, the gearbox must be very strong, and so it is

normally made from fully-stressed magnesium. Now, they produced gearbox casings

made from carbon-fibre. This helped weight distribution but caused many

problems related to heat and the forces imposed by the suspension arms. Titanium

having advantages of a 5 kg decrease in mass when compared with forged

magnesium.

Gear

cogs or ratios are used only for one race, and are replaced regularly during

the weekend to prevent failure, as they are subjected to very high degrees of

stress. The gear ratios are an important part of the set-up process of the car

for each individual track. The teams will adjust the final gear (sixth or

seventh depending on how many gears their gearbox have) so that the car will

just be approaching the rev limit at the end of the straight. (For the race it

will be a few revs less than the limit to allow for the revs to rise in the

slipstream of another car.) Next, the lowest gear needed on the track will be

adjusted to give the best acceleration out of that corner, and then the other

gears will be chosen so that they are spaced out equally between the two

pre-determined gears.

F1

cars have a reverse gear, but these are designed to satisfy the regulations

rather than being of much practical use. Most teams build a very small and

flimsy reverse gear on the outside of the gearbox to help keep the weight of

the gearbox down, as reverse gear is seldom used Each gear change is controlled

by a computer, taking between 20-40 milliseconds. The gearbox is built to

enable the mechanics to easily change the ratios, as they can even be dependent

on the wind direction.

6.5.4 DIFFERENTIAL

To

enable the rear wheels to rotate at different speeds around a corner, F1 cars

use differentials much like any other forms of motorized vehicle. Formula One

cars use limited-slip differentials to help maximize the traction out of

corners, compared to open differentials used in most family cars. The open

differential theoretically delivers equal torque to both drive wheels at all

times, whereas a limited slip device uses friction to change the torque

relationship between the drive wheels. Electro-hydraulic devices are used in F1

to constantly change the torque acting on both of the drive wheels at different

stages in a corner. This torque relationship can be varied to 'steer' the car

through corners, or prevent the inside rear wheel from spinning under harsh

acceleration out of a bend.

A Moog valve will constantly adjust the

friction between the two shafts around the track to maximize the performance of

the car dependent on what characteristics have been entered into the on-board

computer. The Moog valve opens and closes depending on what the software is

telling it to do, but the valve must work to the same set of conditions that

are pre-programmed whilst the car is in the pits. This means that the driver

cannot actually alter the characteristics of the differential due to a change

in tracks conditions for instance.

7. TYRES AND WHEELS

7.1 TYRES

F1 tyres must be able to withstand very

high stresses and temperatures, the normal working temperature at the contact

patch is around 125 degrees Celsius, and the tyre will rotate at about 3000 rpm

at top speed. The tyres are filled with a special nitrogen rich, moisture free

gas to make sure the pressure will not alter depending on where it was

inflated. The tyres are made up of four essential ‘ingredients’: carbon blacks,

polymers, oils and special curatives. During a race weekend, the teams can

choose between two compounds of dry tyres to use during qualifying and the

race. Normally, a hard and a softer compound tyre will be brought to the rack,

with the teams deciding before qualifying which compound to use for the rest of

the weekend. The softer tyre will give a bit more grip, but will wear and

blister more quickly than the hard tyre.

The picture on below shows

the three types of tyres that can be used.. The dry tyre has four

circumferential grooves to reduce the 'contact patch' that decreases cornering

speeds. The wet tyre can only be used when the track is declared officially

'wet' by the Stewards of the race. This tyre type must have a 'land' area of

75% (the area that touches the track) whilst the channels to remove the water

must make up the remaining 25% of the tyre area. The intermediate tyre is used

during changeable conditions when it is still slightly damp. If a wet tyre is

used when the track is not actually very wet, the tread overheats, losing grip.

An intermediate choice channels out water without overheating as much as a wet

tyre.

Tyres

are of paramount importance on a racing car as they are the sole suppliers of

grip. Each tyre has about the area of an adults palm touching the ground, (this

area is called the contact patch) and this area must be maximized by the

suspension to create as much grip as possible. The set-up of the car's

suspension is designed to maximize the contact patch during cornering,

acceleration and braking. Although there are some variables involved with the

tyres, most of the factors that control the behavior of the contact patch are

induced by the suspension set-up.

The

pressure of the tyres is a critical factor in the car's performance. As well as

determining the amount of lateral movement of the tyre, the pressures are

critical to the movement of the suspension. As the tyre walls are so large,

about half of the vertical movement of the car comes from the squashing of the

tyre walls, with the rest in the springs or torsion bars in the suspension.

F1

tyres, as with most tyres today are radial in design. These are advantageous

over bias design tyres as the side walls are allowed to flex, keeping the

contact patch of the tyre stuck to the ground. This can lead to adverse

handling as they may break away from traction quickly. Early race cars used

bias tyres as they were more predictable in their handling characteristics, but

technology has advanced and radial tyres have developed into a much better

design and are used commonly.

Current F1 tyres must have four grooves

around them to comply with the rules which were issued as a way on controlling

the cornering speed of the cars. The picture above shows the dimensions of the

grooves:

7.2 WHEELS

F1

wheels are usually made from forged magnesium alloy due its low density and

high strength. They are machined in one piece to make them as strong as

possible, and are secured onto the suspension uprights by a single central

locking wheel nut. This 'lock' is quickly pushed in to release the wheel during

a pit stop, and the tyre changer then pulls it again to lock the wheel once the

tyres have been changed.

.

Once at the track, teams deliver their bare wheel rims to the tyre manufacturers’

truck where the tyres are put onto the rims with special machines. The tyres

are then inflated and delivered back to the teams.

7.2.1 WHEEL TETHERS

F1

cars have had to fit wheel tethers connecting the wheels to the chassis. This

rule was introduced to try to stop wheels coming free and bouncing around

dangerously during an accident. The tether must attach to the chassis at one

end, with the other end connecting to the wheel hub.

The tethers used in F1 are a derivative of

high performance marine ropes, made especially for each car. They are made from

a special polymer called polybenzoaoxide (PBO) which is often called Zylon.

This Zylon material has a very high strength and stiffness characteristic

(around 280GPa) much like carbon, but the advantage of Zylon is that it can be

used as a pure fibre unlike carbon which has to be in composite form to gain

its strength. The drawback of Zylon is that is must be protected from light, so

it is covered in a shrink wrapped protective cover. The tethers are designed to

withstand about 5000 kg of load, but often they can break quite easily during

an accident, especially if the cable gets twisted by the broken suspension

members. The teams normally replace the tethers every two or three races to

ensure that they can withstand the loads put on them during an accident.

8. THE SUSPENSIONS

The

setup of a cars suspension has a great influence on how it handles on the

track, whether it produces under steer, over steer or the more useful neutral

balance of a car. On an F1 car, the suspension must be soft enough to absorb

the many undulations and bumps that a track may possess, including the riding

of some vicious yet time-saving curbs. On the other hand, the suspension should

be sufficiently hard so that the car does not bottom out when traveling at 200

mph with about 3 tons of downforce acting on it.

Most

of the team's suspension systems are similar, but they take two forms. The

first is the traditional coil spring setup, common in most modern cars. The

second is the torsion bar setup. A torsion bar does the same job as a spring

but is more compact. Both forms of suspension are mounted on the chassis above

the driver’s legs at the front of the car, and on top of the gearbox at the

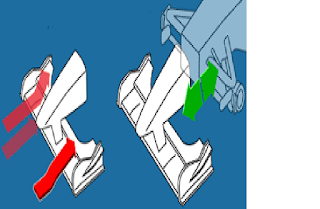

rear. The pictures below left show the typical suspension setup and the spring

and a torsion bar:

A

bump is absorbed by the spring compressing, and then contracting. A Torsion bar

absorbs a bump by twisting one way, then twisting back.

8.1 SPRINGS & TORSION BARS

The

springs or torsion bars are the parts of the suspension that actually absorb

the bumps. In simple terms, the softer the suspension on the car, the quicker

it will travel through a corner. This has the adverse effect of making the car

less sensitive to the drivers input, causing sloppy handling. A harder sprung

car will have less mechanical grip through the corner, but the handling will be

more sensitive and more direct.

To

gain more grip, the engineers cannot simply soften the springs all round. This

may increase grip up to a point, but there are many adverse effects that will

occur. Firstly, the car may bottom out when under the influence of aerodynamic

load when traveling at high speed. Secondly, the car will suffer body-roll in

the corners which will influence the angle of the tyres with the road, reducing

overall grip. The final point is that the car will pitch forwards and backwards

under the influence of hard acceleration or braking. This effect the cars

aerodynamics, especially the grip obtained from the airflow under the car.

8.2 DAMPERS

Often

called shocks absorbers, dampers provide a resistance for the spring to work

against. The purpose of this is to prevent the spring from oscillating too much

after hitting a bump. Ideally, the spring would contract over a bump, and then

expand back to its usual length straight afterwards. This requires a damper to

be present as without one the spring would contracted expand continually after

the bump, providing a rather horrible ride The way that dampers operate can be

tuned to alter the handling. The 'bump' and 'rebound' characteristics can be

altered to control how quickly they contract and expand again.

8.3 PACKERS AND BUMP RUBBERS

Packers

or bump rubbers can be used to prevent the springs or torsion bars compressing

too far. This allows the suspension to be soft, but it means the bottom of car

can only get a certain distance towards the ground until the springs hit the

bump rubbers down a straight. Cars often run on these bump rubbers under the

influence of high speed aerodynamic load, but they must not come into play

around a corner. If the suspension is soft enough for the car to ride the bump

rubbers around a corner (not just a flat out curve) the movement in the

suspension cannot give the wheel the desired grip, so the car's handling in the

corner is compromised. They are useful on modern cars to preserve the wooden

plank under the car, the rules stating that no more than 1 mm can be worn

during the race.

8.4 ANTI - ROLL BARS

Anti-roll

bars are used to stiffen the way the cars roll in a corner. As speeds increase,

the gravitational effect of a change in direction wants to roll the body off

the car towards the outside of the corner. As the body rolls, the suspension contracts

on one side and expand on the other to keep the wheels touching the road. As

the suspension is mounted on the body, now at an angle, the whole system is

rotated to one side. This produces a cambered effect on the tyres, with the

contact patch being reduced, cutting grip. Diagram 1 below shows the car on a

straight, while diagram 2 shows the car in a corner. The body roll can be

reduced by installing anti-roll bars. These connect the left hand suspension to

the right hand suspension so that the springs can only move together. This

prevents the body roll, as now one side cannot contract while the other side

extends as in diagram 2 below. These are adjustable to give different amounts

of movement, and can be adjusted to give various handling characteristics.

DIAGRAM 1 DIAGRAM 2

The

pitch situation is very difficult to over come. It is unfeasible to link the

front and back together in the same way as the two sides of the suspension are

linked as in anti-roll bars. In general, longer wheelbase cars are less pitch

sensitive.

9. THE BRAKES

F1

cars use disc brakes like most road cars, but these brakes are designed to work

at 750 degrees C and are discarded after each race. The driver needs the car to

be stable under heavy braking, and is able to adjust the balance between front

and rear braking force from a dial in the cockpit. The brakes are usually

set-up with 60% of the braking force to the front, 40% to the rear. This is

because as the driver hits the brakes, the whole weight of the car is shifted

towards the front, and the rear seems to get lighter. If the braking force was

kept at 50% front and rear, the rear brakes would lock up as there would be

less force pushing the rear tyres onto the track under heavy braking.

For

qualifying, when longevity of the brake discs is not important, teams often run

thinner discs to reduce the weight of the car. Race discs are 28 mm thick (the

maximum allowed) where the special qualifying discs are often as thin as 21 mm.

Teams often run either very small or in some cases no front brake ducts during

qualifying to gain an aerodynamic advantage.

The

rotating discs are gripped by a caliper which squeezes the disc when the brake

pedal is pushed. Brake fluid is pushed into pistons within the caliper which

push the brake pads towards the disc and pushes against it it slow the wheel.

The discs are often drilled so that air will flow through and keep the

temperature down.

These

master cylinders contain the brake fluid for both the front and rear brakes.

The front and rear systems are connected separately so if one circuit would

fail, the driver would still have either the front or rear system with which to

slow the car. Also visible is the steering rack and the plumbing for the power

steering system.

9.1 BRAKE MANUFACTURE

These

brakes are extremely expensive as they are made from hi-tech carbon materials

(long chain carbon, as in carbon fibre) and they can take up to 5 months to produce

a single brake disk. The first stage in making a disc is to heat white poly acrylo

nitrile (PAN) fibres until they turn black. This makes them pre-oxidized, and

are arranged in layers similar to felt. They are then cut into shape and carbonized

to obtain very pure carbon fibres. Next, they undergo two densification heat

cycles at around 1000 degrees Celsius. These stages last hundreds of hours,

during which a hydrocarbon-rich gas in injected into the oven or furnace. This

helps the layers of felt-like material to fuse together and form a solid

material. The finished disc is then machined to size ready for installing onto

the car.

Carbon

discs and pads are more abrasive than steel and dissipate heat better making them

advantageous. Steel brakes are heavier and have disadvantages in distortion and

heat transfer. Metal brake discs weigh about 3 Kg; carbon systems typically 1.4

Kg. Metal brakes are advantageous in some aspects such as 'feel'. The driver

can get more feedback from metal brakes than carbon brakes, with the carbon

systems often being described like an on-off switch. The coefficient of

friction between the pads and the discs can be as much as 0.6 when the brakes

are up to temperature. You can often see the brake discs glowing during a race;

this is due to the high temperatures in the disc, with the normal operating

temperature between 400-800 degrees Celsius.

10. STEERING WHEEL & PEDALS

A

sophisticated steering wheel with all the information that was usually mounted

on the dashboard fitted to the front of the steering wheel it made from

carbon-fibre with a suede grip. Due to the tight confines of the cockpit, the

wheel must be removed for the driver to get in or out, and a small latch behind

the wheel releases it from the column. The picture on the right shows Ferrari

wheel complete with all the buttons and switches. On the front of the wheel are

mounted items such as rev lights, fuel mixture controls, speed limit button,

radio button and more complicated functions like electronic differential settings

Levers

or paddles for changing gear are located on the back of the wheel. Most drivers

use the left-hand paddle to change down and the right to change up. And some

uses his right hand only to change gear, pushing the paddle away to change up,

and towards him to change down. Below the gear paddles are located the clutch

levers. There is one on each side although they both perform the same function.

Some uses a large paddle on the left of the wheel to control his clutch. These

paddles can be seen on the some wheel to the left. Paddle 1 is the up shift

whilst paddle 2 is the downshift. The clutch levers are located below the

gearshift paddles. Having the clutch on the steering wheel allows the pedal box

of the car to be less cluttered and makes it easier for drivers to left foot

brake.

The

pedals of an F1 car are usually designed specifically for each driver. Some

like large brake pedals and small accelerators, others have small lips on the

side of the pedals so each foot is held in position on the pedal. Most drivers

use left foot braking and so have just two pedals, while those that use their

right foot to brake will have small foot rest for their left foot to help

support themselves under braking.

1. Regulates front

brakes

2. Regulates rear

brakes

3. Rev Shift lights

4. 5 lap time display

6. Neutral gear buttons

7. Display for Gear,

engine RPM, water & oil temperatures

8. Engine cut-off

switch

9. Place to add small

map of track with sector breakdowns

10. Activates drink bottle pump

11. Brake balance selector

12. Manual activation of fuel door

13. Air / fuel mix selector

14. Power steering servo regulator

15. Specific car program recall

16. Engine mapping selector

17. Selection 'enter' key

18. Electronic throttle regulators

19. Change menus on display

20. Pits to car radio activation

21. Pit lane speed limiter activation

11. TECHNICAL TELEMETRY

OVERVIEW

Every

one of the 22 Formula One cars on the grid is dependent upon sophisticated

electronics to govern its many complex operational systems. Each Formula 1 car

has over a kilometer of cable, linked to about 100 sensors and actuators which

monitor and control many parts of the car. Rarely a race goes by without a car

retiring with electrical problems, indicating the important role that this

technology has in modern F1 cars.

11.1 ENGINE MANAGEMENT

The

800 bhp of a modern F1 engine is largely a result of a complex electronic

control unit (ECU) that controls the many systems inside an engine so that they

work to their maximum at every point around the lap. Engine mappings can change

completely from circuit to circuit depending upon the nature of the track. For

instance, the engine control system will help the driver have more control on

the throttle input by making the first half of the pedal movement very

sensitive, and the latter half less sensitive. This means that the driver can

have great control on the throttle for the twisty corners, so that it is easier

to limit the acceleration out of corners so not to spin the wheels. The

accelerator will be set so that only a small movement will result in full

engine acceleration. It is also possible to iron out any unplanned movements of

the throttle such as when a driver travels over a bump and his foot may move

slightly. The engine control system can cut out the jumps of the throttle and

keep full throttle down the straight, even on bumpy tracks. This is all

possible because there is no direct link between the engine and the

accelerator. The accelerator position is sensed using an actuator, and this

signal is then sent to the engine control system, from where it is passed onto

the engine. An engine ECU is much more than a device for making the throttle

more or less sensitive. The ECU controls the inlet trumpet height, fuel injection

among other things to try to get the maximum torque out of the engine. In the

modern world of electronics, the ECU monitors many of the engine parameters

including RPM, to control the torque output from the engine. This means that

the modern day F1 accelerator acts more like a torque switch than a simple fuel

input controller. F1 engines are so complex that they are designed to run in a

small power band between 15000 - 18000 rpm, and the electronic monitoring and

controlling of the engine parameters are crucial in keeping the engine in this

working region. This working region is where torque is virtually constant, and

letting the engine get below the lower limit would see a sudden drop off of

torque, until the engine began to rev in the working region, where the torque

would come in suddenly again, probably promoting wheel spin.

11.2 OTHER ROLES OF THE ECU

The

ECU also controls the clutch, electronic differential and the gearbox. The

clutch is controlled by the driver to start the car from rest, but not during

gear changes. Although the driver modulates the throttle like on a road car

(although with his hand) there is no direct link to the clutch - it is all

electronic. The ECU engages and disengages the clutch as the driver moves the

paddle behind the steering wheel. The ECU will also depress the clutch if the

car spins to stop it stalling. They introduced the anti-stall device to prevent

cars stalling after a spin and being left dangerously i the middle of the

track. The ECU is also responsible for changing gears in fewer than 100 milliseconds.

The electronics allow the driver to keep his foot flat on the throttle during

up-shifts, and blip the throttle on down-shifts to match engine speed with

transmission speed to prevent driveline snatch. The final area controlled by

the ECU is the differential. Modern F1 cars have electronic differentials which

monitor and control the amount of slip between the rear wheels on entry and

exit of corners. This is often adjusted for different driving styles to try to

keep the rear end of the car in control during all phases of a corner.

11.3 DATA ACQUISITION - TELEMETRY

Every

aspect of the car, whether it be speed, brake and engine temperature,

suspension movements, ride height, pedal movements and g-force are measured and

controlled from the pit whilst the car is out on the track. Teams usually take

over 30 kg of computer equipment to help the drivers and engineers to find the

right set-up and cure any car problems. An F1 car has two types of telemetry:

The first is a microwave burst that is sent to the engineers every time the car

passes past the pits. This data burst can contain around 4 megabytes of

information giving the engineers a vital insight into the state of the car.

Another 40 or so megabytes can be downloaded from the car when it returns to

the pits, so no part of the car goes 'unwatched'. The information is downloaded

by plugging in a laptop computer to the car, in a socket usually located in the

sidepod or near the fuel filler. The second type is a real time system which

transmits smaller amounts of information, but this time it is in 'real time'.

This means the car is constantly sending out information such as its track

position and simple sensor readings. The telemetry is sent to the pits via a

small aerial located on the car, usually located on the sidepod nearest to the

pits. Some teams have placed the transmitter in the wing mirror that passes

closest to the pits to do away with an extra aerial. When the cars returned to

the pits, a small box was put over the wing mirror to prevent anyone being

harmed by the radiation given out by the transmitter. This telemetry data is

vital to the engineers both during the race and practice. A huge bank of

computers at the back of the garage will process the information sent by the

cars whilst they are on the track, and from this complex information, the team

members can quickly tell whether the car is operating correctly. During a race

for example, readings such as the engine temperature and hydraulic pressure are

carefully examined lap by lap to ensure the car is not about to suffer any

major failure. If any of one of these readings becomes varied from the normal

operating state, the engineers can tell the driver to use less engine revs or

drive more steadily to try to prevent a failure. Teams use software that will

display all of the gathered information on a screen that can be easily

interpreted by the engineers.

11.4 THE RADIO

One

of the hidden aspects of F1 Car racing is the radio system used both in the car

and all around the race course. At a typical race there are several thousand

one-way and two-way radios sharing the airwaves. They transmit data from the

car and the driver, allow the teams to communicate with one another and even

let the tires transmit their pressure to the onboard data computer. A typical

car has as many as eight radios in operation at any one time:

The driver's two-way radio

The telemetry system's radio

The radio(s) for on-board television

cameras

The radios for the tires

12. COSTS

HOW MUCH DOES AN F1 CAR COST TO MAKE?

This is one of the most commonly asked

questions by spectators and this section will try to get an overall total to

design and build one Formula 1 car. The table below outlines the main parts of

the car and how much each part costs:

Each part costs:

PARTS AMOUNT SINGLE PRICE (€) AMT. NEEDED TOTAL(€)

Monocoque 112 360 1 112,360

Bodywork 8026 1 8,026

Rear Wing 12842 1 12,842

Front Wing 16051 1 16,051

Engine 240770 1 240,770

Gearbox 128411 1 128,411

Gear Ratios (set) 112360

1 112,360

Exhaust System 9631 1 9,631

Telemetry 128411 1 128,411

Fire Extinguisher 3210 2 6,420

Brake Discs 964 4 3,856

Brake Pads 642 8 5,136

Brake Callipers 16051 4 64,205

Wheels 1124 4

4,496

Tyres 642 4

2,568

Shock Absorber 2087 4 8,346

Pedals (set) 1605 1 1,605

Dashboard 3210 1

3,210

Steering System 4815 1 4,815

Steering Wheel 32103 1 32,103

Fuel Tank 9632 1 9,632

Suspension 3210 1 3,210

Wiring 8026

1

8,026

GRAND TOTAL €926,490

In addition to the build costs, thousands of pounds

will be spent on designing the car. Design costs include the making of models,

using the wind tunnel and paying crash test expenses etc. The cost of producing

the final product will be € 7,700,000

13. Random Facts

-In an F1 engine revving at 18,000 rpm,

the piston will travel up and down 300 times a second.

-Maximum piston acceleration is

approximately 7,000 g (humans pass out at 7-8 g) which puts a load of over 3

tons on each connecting rod.

-The piston only moves around 50 mm but

will accelerate from 0 - 100kmph and back to 0 again in around 0.0025 seconds.

-If a connecting rod let go of its

piston at maximum engine speed, the piston would have enough energy to travel

vertically over 100 meters.

-If a water hose were to blow off, the

complete cooling system would empty in just over a second.

Modern

engines have a mass less than 100 kilograms and are deigned to be as low as

possible to reduce the overall centre of gravity of the car. The engine must be

as light as possible, but also as stiff as possible. This is because the only

thing connecting the rear of the car to the chassis is the engine, so it must

be able to take the huge cornering loads from the suspension and aerodynamic

forces from the large rear wing. The engine is fixed to the chassis with only

four high strength suds, and is connected to the gearbox with six of these

studs. There is a new trend in engine design, opening up the V-angle beyond 100

degrees. This allows the engine to sit lower in the car, reducing the centre of

gravity, but the unit is currently suffering problems due to vibration and lack

of stiffness.

14. CONCLUSION

Handling a Formula1Car is nothing like a normal automobile

the goal is to adjust all of these variables in concert with one another to

create the perfect setup. The car’s engine, suspension, aerodynamics, tires,

etc. determine how fast they go. But that the sanctioning bodies of these race

series are, trying to slow the cars down in an attempt to maintain safety and

reach a good level of competition. Working in a F1 group requires precision, incredibly

fast reflexes and endurance obviously this is not easy because all of the

variables have interrelationships with one another. Getting the car tuned and

keeping it in a state of perfection is two of the team's most important tasks

during the season. On the day of the race, the team hopes that everything with

the car and the driver is perfect and that the result of all of this

preparation is a win.

The engineering of materials, cooling system

aerodynamics, heat insulation, and the high temperature structural stiffness of

Formula 1 components is leading-edge technology. Even equipped with all this

advanced systems engineering, however, the driver experiences problems in

controlling the powerful system during the 2-3 seconds in which he slows the

car and sets it up for a corner. The problem is currently at the forefront of

the minds of Formula 1 engineers

part costs:

Design costs include the making of models, using the wind tunnel and paying crash test expenses etc.

The cost of producing the final product will be €7.700.000,-. Better start saving...

15. REFERENCES

1. http://www.formula1.com- The Official Website

2. http://www.f1world.com

3. http://www.motorsportengineering.com

6.

http://www.jdsport.com/motorsports/auto_racing/formula_one/technical.html

9. Formula1 Technology by Peter Wright

10. Performance at the limit: Lessons from

f1 motor racing by

Mark Jenkins, Ken Pasternak,

Richard West

EmoticonEmoticon